In the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit.

In the gospel reading, we are told that Christ went up into a mountain apart to pray. There are about two dozen references to Christ praying in the gospels, and there’s nothing in the Scriptures that is there without some significance. Even the smallest details have some meaning. We may not always know what that meaning is, but there is meaning there. Christ lived the life that we have been unable to live. He lived a perfect life, and he was a model for us to follow. Obviously, prayer is a key part of the Christian life.

In the gospels there are two places where Christ taught his disciples the Lord’s Prayer. In the Gospel of Luke he taught them the prayer, we’re told, in response to the question, “Lord, teach us to pray as John also taught his disciples.” So this is a very important prayer. It’s a model prayer. It’s a prayer that we pray every day. But there are many elements in it that we probably have never thought about why they are there or what they really mean. It’s important for us to pray with the understanding, pray and understand what it is that we’re saying.

A little bit more than a decade ago, I preached a series of sermons on the Lord’s Prayer, and I’m going to repeat that, although not word-for-word. I’ve gotten a few commentaries from the Fathers since then, so it won’t be the same set of sermons, but also a lot of you weren’t here to hear that back then, and if you were you probably have forgotten a lot of it.

So we’re just going to go ahead today and talk about just the first part of that prayer: “Our Father, who art in the heavens, hallowed be thy name.” First of all, to address God as “Father” is a bold thing. It’s something that is not taught in the Old Testament. It’s something that was not revealed to the Israelites. There are two places in the prophecy of Isaiah where he speaks of God as a father. That’s the only inklings of this teaching, but never were there prayers that the Israelites were taught that began with an address or included an address to God as their father. So it’s one part of Christ’s teaching that is undoubtedly a new revelation. As a matter of fact, German biblical scholars who are not known for being the most faithful, they tend to take a very skeptical approach to the gospels, but one of them, Joachim Jeremias, concluded that this is one part of Christ’s sayings we know for sure that he said, because there’s no way that they would have made this one up.

Addressing God as “Father” is something that begins with Christ. He’s teaching us to do that. But what does it mean for us to address God as “Father”? Christ is the Son of God in a sense that we cannot be the son of God; he was the Son of God by nature. But we can become God’s sons and daughters by adoption. At the beginning of the Gospel of John, we’re told, “But as many as received him, to them he gave the power to become the sons of God, even to them that believe on his name which were born not of blood nor of the will of the flesh nor of the will of man, but of God.” And in the epistle to the Romans, St. Paul tells us:

For as many as are led by the Spirit of God, they are the sons of God. For ye have not received the spirit of bondage again to fear, but ye have received the spirit of adoption whereby we cry: Abba, Father! The Spirit itself beareth witness with our spirit, that we are the children of God. And if children, then heirs, heirs of God and joint-heirs with Christ. If it so be that we suffer with him, that we may be also glorified together.

When St. Paul says, “Abba, Father,” he’s using an Aramaic word and then he’s repeating the meaning of that in Greek. It’s interesting in the gospels, there’s one place where, in the Gospel of Mark, Christ is quoted also as saying, “Abba, Father,” but undoubtedly he probably stuck with one language, but the gospel writer, St. Mark, wanted us to know what it was that he was saying, but he also wanted to let us know what he actually said in the language that he spoke.

“Abba” is not the technical term for a father. When we talk about on a birth certificate it says, “Father” or “Mother”—at least it used to say that until recently, when we forgot that it takes a father and a mother to produce a child. But on your birth certificate, it says, “Father,” but I didn’t talk to my father by saying, “Father, how are you doing today?” I would say, “Dad, how are you doing today?” Many of you might have had different ways of referring to your father, but we have loving terms of endearment that express our familiarity with our father, because we’re his children. So we might say, “Daddy,” or we might say, “Papa,” but these are words of endearment. Well, “Abba” is the Aramaic word for that. You can say, “Daddy.” So when Christ taught us to pray, “Our Father,” it was not even “Father” in a remote sense, but “Father” in an intimate sense.

If God is our Father, then that means that we’re supposed to be like him. To live like a child of the devil and then to call God your father is blasphemy. Earlier in the Sermon on the Mount, Christ taught, “Be perfect even as your Father which is in heaven is perfect.” Of course, Christ was not calling us to be perfect in the infinite sense in which only God can be perfect, but we’re told by St. Paul that we can be perfect in love. That’s what we’re called to do is to always be guided and have our actions governed by love, and that is something that’s possible for us to do, though most of us fall short of that on a daily basis.

But if we have fallen short, how can we come back to our Father and address him as “Father”? Well, we can do that the way that the prodigal son did so. “Father, I have sinned against heaven and before thee, and I’m no more worthy to be called thy son. Make me as one of thy hired servants.” When we come to God in repentance and then we call him “Father,” we’re coming to him like the prodigal son, and God doesn’t reluctantly receive the prodigal son. We’re told that he came running to him, to meet him on the road.

And what did he say? He said, “Bring forth the best robe and put it on him, and put a ring on his hand and shoes on his feet. Bring hither the fatted calf and kill it, and let us eat and be merry. For this my son was dead, and is alive again; he was lost, and is found.” St. Gregory of Nyssa tells us that the robe that the prodigal son is dressed in is the first robe, the robe of righteousness, which he was deprived of by his disobedience. And the ring signifies the regaining of the image of God. The shoes are there to protect him from the bite of the serpent, the devil. And when it says, “Bring hither the fatted calf,” who is the fatted calf? The fatted calf is Christ himself. We partake of the body and blood of Christ, and we’re united with him. So when we come to God in repentance, that’s how we’re received.

But what does it mean and why do we say, “Our Father”? It doesn’t say, “My Father in heaven”; we say, “Our Father.” When we say, “Our Father,” we’re acknowledging that we don’t have a relationship with God as Father that is apart from our relationship with his children. We have a relationship with the Church. St. Cyprian of Carthage, one of the early martyrs of the Church, said, “He cannot have God as his Father who does not have the Church as his Mother.” If you’re an Orthodox Christian, God is your Father, and the Church is your Mother, and you were begotten by the Father, and the Church gave birth to you in the womb of the baptismal font.

You may be living like a true son or daughter of God, or you may be living like the prodigal, but that’s the basis of your ability to call God your Father. God is not the Father of everybody. God is the Creator of everybody, and God calls everyone to become his children, but those that have not accepted him as Father are not his children, and they cannot say this prayer and have it be something other than a sin. But if you come to God in repentance, you can; he will accept you as his child by adoption.

Then there’s the phrase, “Who art in the heavens,” is the way we say it, and if you’re wondering why we say, “In the heavens,” that’s because that’s exactly what it says in Greek. Most translations say, “Who art in heaven,” and that’s a defensible translation into English, but the literal translation is, “Who art in the heavens.” This doesn’t mean that God is limited to some space out there and that he’s absent everywhere else, but this does tell us that heaven is our homeland. Heaven is where God rules, but this is not limited to a particular place. If we allow God to rule us, then the kingdom of heaven is within us, too. Christ tells us in the gospels, “The kingdom of God cometh not with observation; neither shall they say, “Lo, here,” or “Lo, there.” Behold the kingdom of God is within you.”

So heaven is all around you. Whether you are connected with that is the other question. We participate in heaven in the Divine Liturgy every time we serve it. That’s the reason why we begin the Liturgy with: “Blessed is the kingdom,” because we are entering into the kingdom of God in a very special way. We are stepping outside of time and into eternity, and we are beginning to participate in the life of heaven in the Liturgy. So that’s what it means, but if you allow this to get in here, then you can carry the kingdom of heaven with you wherever you go.

And then it says, “Hallowed be thy name,” so you could literally translate that, “Holy be your name,” or “May your name be sanctified”—but what does that mean? It obviously does not mean that God has some lack of holiness, and that by our prayers we’re adding to that. There’s no holiness that we can add to God, so what does it mean? In the Old Testament, many times God, through his prophets, spoke of the people of Israel as the people called by his name. In the New Testament, we’re called Christians. So when we’re called Christians, we are literally bearing the name of Christ everywhere we go. But the Christians say, “But the name of God is blasphemed among the Gentiles because of you.” So when we are people called by God’s name but we fail to live up to what that means, when we fail to live the life of God, the life of Christ, then people look at us and they say, “Well, these Christians are no different [from] other people.” They might even say, “These Christians are worse than other people.”

So when we say, “Hallowed be thy name,” we’re saying, “May we make your name holy. May other people make your name holy,” but primarily we want to be focused on us, because we can’t control other people, but we can control ourselves. The commandment against taking the name of the Lord in vain, it certainly includes speaking about God in a blasphemous way or in a careless way, but primarily what it means to take the name of the Lord in vain is to call yourself a Christian when you don’t really live a Christian life, when you don’t live a life that goes along with calling yourself a Christian. You’re taking that name in vain, and that’s a violation of that commandment.

So if we’ve done that, if we’ve failed to make God’s name holy by our actions, what do we need to do? We need to return to our heavenly Father like the prodigal son. “Father, I have sinned against heaven and before thee,” and he will receive us. Let us live like true children of our Father, striving to be perfect in love, for God and for our neighbor, allowing the kingdom of heaven to truly reign in our hearts, and so let your light shine before men, that they may see your good works and glorify your Father which is in heaven. Amen.

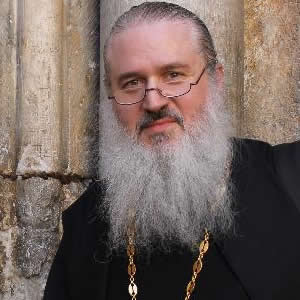

Fr. John Whiteford

Fr. John Whiteford