In the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit.

Today we celebrate the feast of all the saints of Russia, and this feast was appointed by the Russian Church at the 1917-1918 Sobor because of the persecution that they saw coming, and they wanted to call upon the saints of the Russian Church to pray for their land, that God would see them through this time of persecution. We can thank God that those prayers were heard. During the vigil last night, those of you that were here would have noticed that the canon was quite a bit longer than usual, not that there were more troparia, but that each troparion was quite a bit longer, because they were trying to squeeze in so many references to so many saints of the Russian Church, and they were only really hitting the highlights of the saints of the Russian Church, because you could only scratch the surface of all these saints.

But I want to talk about one saint in particular, one that is very important to us here in America, and that’s St. Innocent of Alaska, as he’s usually known in the United States, or St. Innocent of Moscow, as he’s known more commonly in Russia. He was born with the name John Popov, and he was born in 1797, a few years after the first missionaries had arrived in Alaska, and he was born in a remote village in Irkutsk in southeast Siberia to a very poor family of the local church’s sexton. A sexton would be someone who would ring the bells, maintain the property; he might serve in the altar. So he would have been the lowest rank of someone who would have gotten any kind of a salary from the church. People who were usually clergymen attached to churches didn’t make great money in the best of cases, even when they were the priest, but when they were that low on the totem pole, it was pretty meager fare.

His father passed away when he was six, and then he went to live with his uncle who happened to be the deacon at that parish. In 1807, at the age of 10, he was sent off to seminary. Seminary worked a little different in those days. So from the age of 10 up until about the age of 21, he was engaged in his studies to prepare himself for ordination. He was such a good student that the rector of the seminary changed his last name to Veniaminov in honor of the recently departed but very much loved bishop of Irkutsk, Veniamin. In those days, surnames in Russia were sort of in a state of flux, so this sort of stuff wasn’t as strange as it would seem to us, to have someone change your last name. Surnames were a relatively new thing at this time. But he was such a brilliant student that he could have had an academic career had he chose to have one, but he wanted to get his hands dirty in the practical work of the ministry.

At the age of 20, he married the daughter of a local priest. The clergy kept things in their extended family in those days, and so soon after that he was ordained a deacon. He finished his studies in 1818, and he was appointed as a teacher at the parish school. When he was 23 he was ordained a priest. Now, if you know the canons, these dates are much earlier than the canons advise someone to be ordained a priest, but because of the need sometimes there’s an exception that is made. So he was ordained at 23 rather than the age of 30 or beyond, which is what the canons would have called for.

The bishop was asked by the holy synod in Moscow to send a priest to Alaska, because they needed help with the fledgling mission that was there, and so Fr. John at that time volunteered. After a year-long journey by land and water, he finally arrived at the western Aleutian island, and he resided at the biggest island, Unalaska, and there he moved into an earthen hut with his wife, his infant child, and his mother-in-law, and his brother. While he was there, he regularly would hop into a kayak and sail to nearby islands or sail around an island. That was the best way to get around, but we’re talking about a kayak that might have been made out of walrus skin, and that would have been the only thing separating him from ice-cold water as he sailed from place to place.

He learned six dialects of Aleut; he was a linguistic genius, obviously, and he created an alphabet for them. He used the Cyrillic alphabet, but he had to create additional letters because they had sounds that didn’t exist in Russian. He translated the Gospel of Matthew into Aleut, as well as a catechism and many hymns. It should be noted—let me preface this comment just by stating why I was very impressed when I first read the Life of St. Innocent. I studied to be a Protestant minister and was particularly… had a concentration in missions, because I had a desire to be a missionary. I didn’t know that God would call me one day to be a missionary to my own country, but I had this idea that one day I would go be a missionary in a foreign country, so I studied a lot about missions. And when you study the history of missions, you see many of the mistakes that Protestant missionaries made.

For example, for many years the Protestant missionaries would go to a place like China, and they would expect the locals to learn English, and that’s how they would learn the Gospel. The idea that a missionary would go to a country and learn the language and appreciate the culture and try to appeal to people in a way that would be meaningful to them wasn’t something that occurred to Protestant missionaries, and it took a long time for someone like Hudson Tailor, who was a Protestant missionary that actually got the idea that, yeah, you really do need to try to preach to Chinese people in Chinese, and you’ve got to appreciate their culture if you want to reach out to them.

But St. Innocent was way ahead of that, and Russian missionaries, generally speaking, were. So when he encountered Native Americans, he would see what was good in their culture that could be preserved. He wasn’t just trying to erase their culture; he wasn’t trying to erase their language. There are many native customs that survive to this day among the Orthodox in Alaska that have their origins in their pre-Christian past, but St. Innocent was able to see ways in which these things could be preserved and made to be Christian.

He also wrote a book called The Indication into the Way, the Kingdom of Heaven, which was basically a book about how to become a Christian, what it means to be saved in the Orthodox Church. And he wrote this in Aleut originally, but then he translated it into Russian, because he wanted to send a copy to Russia to have the holy synod approve it, and then have them print the text in Aleut for the natives. When the text was reviewed, it was decided that the text shouldn’t just be printed in Aleut, but that the Russian translation should be printed and that it should be distributed in Russia, because it was such a useful text. As a matter of fact, the text exists in English; you can read it online, but it was one of the first books that I read when I was studying Orthodoxy, and it is a very good book.

He also organized schools, he built churches, and after 10 years he had essentially baptized all the people in the Aleutian islands; all the Aleut people had converted to the faith. He was then transferred to Sitka in 1834, and he began to evangelize the natives that were there, and he had to learn an entirely different native language, Tlingit. There’s no connection that’s obvious between these languages, so he had no leg up on trying to get this, but he mastered that language, and he likewise began translating things into that language.

In 1839, he traveled to St. Petersburg to appeal to the synod to expand the missionary work in Alaska, because he needed help, and he was asking for them to send additional priests to evangelize the people, but while he was there his wife passed away. He got word of that, and he asked for permission just to go back to his hometown and take care of his family, but the emperor was aware of his talents, of his genius, of the work that he was doing, and the emperor recommended that he be made a bishop and sent back to Alaska. At first he resisted, but the metropolitan of Moscow at that time advised him that probably it’s not a good idea to go against the advice of the emperor, and he finally was persuaded. So he became a monastic. His family, of course, was taken care of, but he was made the bishop. At that time he was the bishop of Kamchatka and Alaska, so his diocese actually straddled two continents.

I’m the dean of the Russian Church Abroad for the states of Texas and Louisiana, and it seems like a pretty big area for me to cover, and I think about how long it takes me to drive to places. I can’t even imagine an area that would be more than double that size and have to get around in a kayak or in a reindeer sled or dogsled. He went about, whatever mode of transportation he had, that’s what he used, but that’s how he traveled around his diocese, and he never tired.

I should mention that when he became a monk, he took the name of Innocent, and he took it in honor of St. Innocent of Irkutsk, who was the enlightener of the area that he was born and raised in, and someone that he modeled his life after.

In 1861, he was able to meet with and talk to, in Tokyo, the future St. Nicholas of Japan, the one that established the Church in Japan. So he was able to give him advice and direction. I would have loved to be able to overhear the conversation that the two of them had as they talked about the work that they would do. But these are some of the most successful missionary endeavors, not just in the history of the Orthodox Church, but really in the history of any Christian church. I have a five-volume history of the last two centuries of the Church by a Protestant, and he talks about this. It’s such a notable thing, what St. Nicholas was able to do in Japan. It’s unparalleled by the success of any other Christian group there, with the possible exception of the Roman Catholics before they were largely slaughtered at an earlier time by the Japanese emperor.

The Diocese of Alaska was transferred to Sitka, which is an island that’s actually in Alaska. In 1865, he was made a member of the holy synod, so he was moving up in his rank in the Russian Church and had a great deal to say in the affairs of the entire Russian Church. When his friend and mentor, St. Philaret of Moscow, reposed, he was elected to be his replacement as Metropolitan of Moscow, and so he became the head of the Russian Church. You should understand that at that time there were no patriarchs, because Peter the Great had abolished the patriarchate, but nevertheless, even though he was only a metropolitan by title, he was still the head of the Russian Church.

After the sale of Alaska to the United States, he could have said, “Oh well, all of my work is going to be undone, by the fact that Alaska is now being moved to the United States,” but instead he saw this as a missionary opportunity, and he transferred the diocese from Sitka to San Francisco, and he began to encourage the Russian clergy to translate things and to learn English and to do the services in English. So not only did he do this great work in Alaska and also in Kamchatka—I didn’t even get into that because it’s a whole ‘nother story, but he learned some of their languages there, too, and had things translated into those languages—but he was the pioneer of English-language services in the American Church. He was noted also, I should say, to be a very great preacher. He was very impressive, and no one who heard him preach soon forgot it.

By the time of his repose, the Russian Church was serving in about 120 languages, and quite a few of those languages were the result of his own efforts, to have the services translated into those languages. He reposed on March 31, 1879, and he was buried at the St. Sergius-Trinity Lavra, and I’ve been there twice, and I’ll never forget the first time, as I only had a short period of time—less than two hours—to go around the lavra and see as much as I could take in in that short period of time, when I stumbled across his reliquary and read the Slavonic. My Slavonic is okay, and I can read the text. So I finally figured out, “St. Innocent of Moscow”—that’s him! That’s St. Innocent of Alaska, that’s him! I didn’t know he was buried there. So if you’re ever in Moscow and you go to the lavra, be sure to keep your eye out for that reliquary, so you can venerate his relics.

But one thing that we should take from an example of a great saint like this, and really all the saints of the Russian Church, is that we’re not called to just admire the saints; we’re called to emulate the saints. Just like St. Innocent of Alaska emulated St. Innocent of Irkutsk, we’re called to emulate all these saints and to try to live their example. When you see how much one man accomplished who took his talents and he gave them to God and he dedicated his life to the Church, when you see how much that one man accomplished, just imagine if even one in a hundred of us made the same kind of commitment and the same kind of an effort. What could we not accomplish for the kingdom of God? So each one of us should take that to heart and ask God to show us what we need to do so that we can be like the saints. Amen.

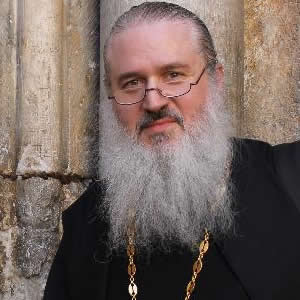

Fr. John Whiteford

Fr. John Whiteford