In the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit.

Today we celebrate the memory of Ss. Peter and Fevronia, the wonder-workers of Murom, and the Russian Church has established this feast to be a Sunday that we focus on the importance of family, love, and fidelity. It’s also a day in which, as I’ve mentioned before, the Church encourages people to get married. This year will be the first time since we established this feast that a couple has taken me up on it, so we’ll be going to do a wedding today. Glory to God.

But what I’d like to talk about is happiness. In the Declaration of Independence, you hear the phrase “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” But it’s interesting that when the Constitution was written, we don’t find “happiness”; we find “life, liberty, and property,” the reason being that happiness and our pursuit of it is something that’s kind of nebulous. It’s difficult to nail down, but property is something that you can actually talk about legal rights to enforce and to protect property.

People pursue happiness, but if you’re pursuing happiness as an end in itself, you’re almost certainly not going to find it. You might find pleasure, and people confuse happiness with pleasure all the time. Pleasure is something that is very temporal; happiness is something that’s an abiding joy. Happiness is what we all want, but if we want it, we need to not seek it, not seek it for ourselves, anyway. As Christ says in the gospels, “For whosoever will save his life shall lose it, but whosoever shall lose his life for my sake and the Gospel’s, the same shall save it.” It’s a paradox. If you want to save your life, you need to lose it; you need to give it up, and that’s how you save it. Well, the same thing comes with happiness. If you want happiness, you need to not seek happiness for yourself, but to seek happiness for other people.

We especially find that in our families. We have a job, a ministry, to seek the good and the happiness of those that are in our families and to be servants to them. There can be great joy that comes out of that. It’s not all joy, but there’s great joy that can be had.

My granddaughter is going to be turning one pretty soon, and I enjoyed my own kids, but there’s something about a grandkid that’s a little bit different. There’s not much that makes me happier than to have that baby sitting on my lap. But when I got that baby sitting on my lap, I’m not getting anything that the baby’s doing for me; my focus is on taking care of her and making her happy, and in that I’m having a great deal of joy, because I’m seeing another generation of people in my family, but also people in the family of God, and I’m getting to play a part in turning this baby into a Christian adult.

We were created to love, and true happiness is only found in love. When we speak of self-love, we need to understand that that’s a manner of speaking, but self’-love is not really love; it’s not love in the agape sense of love that we read about in the New Testament. It’s selfishness. True love requires another person to love. But we as fallen human beings are inclined to the sin of selfishness rather than to love, and that’s why we have to take up our cross and die to ourselves so that we can learn to love.

In Russian there’s a word called podvig, which there really isn’t an exact English equivalent, but it essentially means “ascetic struggle,” so we’ve adopted that word in the Orthodox Church. We talk about podvig, so if you have heard that phrase and have wondered what it meant, that’s what it’s all about. Podvig is something that’s an ascetic struggle. It should be the way we see our whole life, is as a podvig. We are pilgrims that are passing through this land, and we are struggling to attain salvation. We all have different kinds of podvigs, but we all have one, that is, if we are trying to live a Christian life.

Christ says in the Gospel, “Whosoever will come after me, let him deny himself, take up his cross, and follow me.” We have to deny ourselves, and apart from the cross, there is no Christian life. The only way to avoid a cross is to give up on being a Christian. But obviously there’s not a lot of fun, there’s not a lot of pleasure to be had, in that cross itself.

There are two paths for the Christian life, and to some extent we get to choose the cross that we are going to bear when we choose the path that we are going to take, although there are also aspects to the cross that we choose that we can’t see, and we can’t know until we start to experience it. But there are two normal paths, and one is the path to monasticism, and then the other one is marriage. Both of these are good. Monasticism, the Fathers tell us, is an ideal way, it’s a better way for those that are able to accept it. But marriage is also a good thing; it’s something that we should honor and we should uphold and we should respect. The problem is in our day we’ve debased it to where it’s almost a meaningless term, and that’s why fewer and fewer people are even bothering to get married.

But we as Christians have to live out what that means. We need to understand what it means, because marriage is such an exalted thing that in the Scriptures it’s used repeatedly as an image of God’s relationship with his people. A good Christian marriage is an icon to people, and it shows them what that relationship’s supposed to be, so we have to uphold that standard.

But in both monasticism and in marriage, we have the same Gospel. Monastics have to live out the same Gospel that we do, and there’s not a different Gospel for them and one for us; it’s the same Gospel. We have to learn to be humble. We have to learn to die to ourselves. We have to learn to serve others, to love others, and to love God. In a monastery, there are flawed people. If you don’t believe me, spend a little bit of time in a monastery and you’ll see what I’m talking about, but there are flawed people in monasteries. There are people who rub other people in the monastery the wrong way, and they irritate each other; they get on each other’s nerves, and they cause grief. People in the monastery sin against each other.

This is true in a family as well, but these are the situations that allow us to work out our salvation, to learn to be Christians, to learn to be loving, to learn to be forgiving. It’s in this environment that we learn to be patient, to be a Christian. The family is the first place that we all learn that. Even monastics start out in that school house, and that’s where they should be learning these things. Throughout our life, God puts us in situations, and he puts people in our lives for reasons. Often, we say, “Oh, if only that person was gone, I could be a happy person. If I could just get rid of that one person.” But God put that person in your life for a reason, and you need to learn what it is, and you need to try to become a better Christian as a result of it.

One question we should consider in our time is: Why is it that so many marriages even within the Church fail? There are pagans that manage to stay married all their life, and so we Christians should be ashamed of ourselves when we’re not able to make a marriage work, because the only reason why a Christian marriage fails is because one or both of those spouses ceases to live like a Christian. There’s no reason why two Christian people who are united by the sacrament of marriage can’t live together in peace and harmony. People have this Madison Avenue idea of love, and they say, “Well, I was in love with this person, but I don’t love them any more.” But what you have to understand is that love is not the feeling that Madison Avenue is trying to appeal to. That’s a nice warm fuzzy feeling that you have when you first fall in love, but love is a choice. If you stop loving your husband or you stop loving your wife, it’s because you chose to stop loving them; it’s not because Cupid stopped hitting you with the arrow or anything like that. It’s because you chose not to love that person. So don’t go by your feelings; go by the choice.

As a Christian, you’re called to love even your enemies. All the more is that true of those that you’re united with in marriage, because when you’re united in marriage, you become one flesh. That person is connected to you for the rest of your life, and particularly when you have children there’s no getting around the fact that even if you get divorced that you were married to that person, because all your life you’re going to be bumping into that person; as long as you both are still around, that’s going to continue to happen.

It’s a lot better if you stay together and you work it out, and you learn to love each other rather than to have to deal with a broken marriage. Obviously, that takes two. Sometimes one person can do something. It doesn’t matter if they were married to the holiest person in the world; that marriage might still have to end. But if both people are making at least some effort to live out the Christian life and to be what it means to be a Christian, there’s no reason why anyone should ever get divorced.

Christ says in the Gospel, “No man, having put his hand to the plow, and looking back, is fit for the kingdom of God.” And when we are called into marriage, when we enter into that, we have chosen to take up the cross that’s associated with married life. Once you put your hand to that plow, if you look back and you’re not willing to stay committed to that, you’re not fit for the kingdom of God. This is what God has called you to do, and you have to work along with your spouse to establish a Christian home. First and foremost, that means that you need to live out the Gospel yourself, but you also want to be helping your partner along that path. If you both are doing that, that means that both of you are working in a synergistic way to help each other. Then when one is weak, the other one is strong, and vice-versa.

Out of that marriage, hopefully, children are born, and that couple gets to cooperate with God in bringing these children into the Church and into the world and bringing them up in the nurture and admonition of the Lord. You’re cooperating with God. You’re cooperating in the act of creation of another human being, and you get to establish a little church in your home. These things are all wonderful things that we’re called to do. We just need to work on it, because it’s not all sunshine and lollipops. It’s not all easy; it’s a lot of work. But if you put the work in there, there’s a lot of joy there.

We all have more than one ministry in our life, and for each person it’s going to be slightly different. But first and foremost, the ministry that we have is to save the souls of our spouses and our children. This is our greatest and most important purpose in this life, and it’s not easy, especially in our time. It’s not pain-free. It’s a podvig; it’s not a cakewalk. But by keeping your hand to the plow, by not turning your back on the cross that you have chosen and which God has given you for your salvation, you can experience true love, and in this you can find joy and peace.

We don’t find these things by seeking them for ourselves. We find them by looking for joy and peace and happiness for others rather than for ourselves. But by learning to love our families and our neighbors, we learn to love God, and in so doing, and in so losing ourselves, for others’ sake and for God, we save ourselves and find that joy and that peace and that happiness, only to a limited extent in this life, and maybe for some more than others, and for others less. But we will certainly find it in its ultimate and perfect sense, in the next life. Amen.

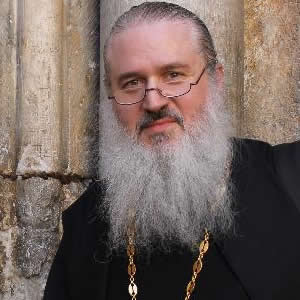

Fr. John Whiteford

Fr. John Whiteford